Q & A with Putin after his Valdai speech

"It is proposed that Mr Blair would head it… I know him personally. I have even visited him at his home, spent the night there, and… over coffee in our pajamas, we spoke at length."

“There were a few cases where I decided that we won’t do anything at all because the damage from acting would be greater than from simply showing restraint and patience.” - Putin

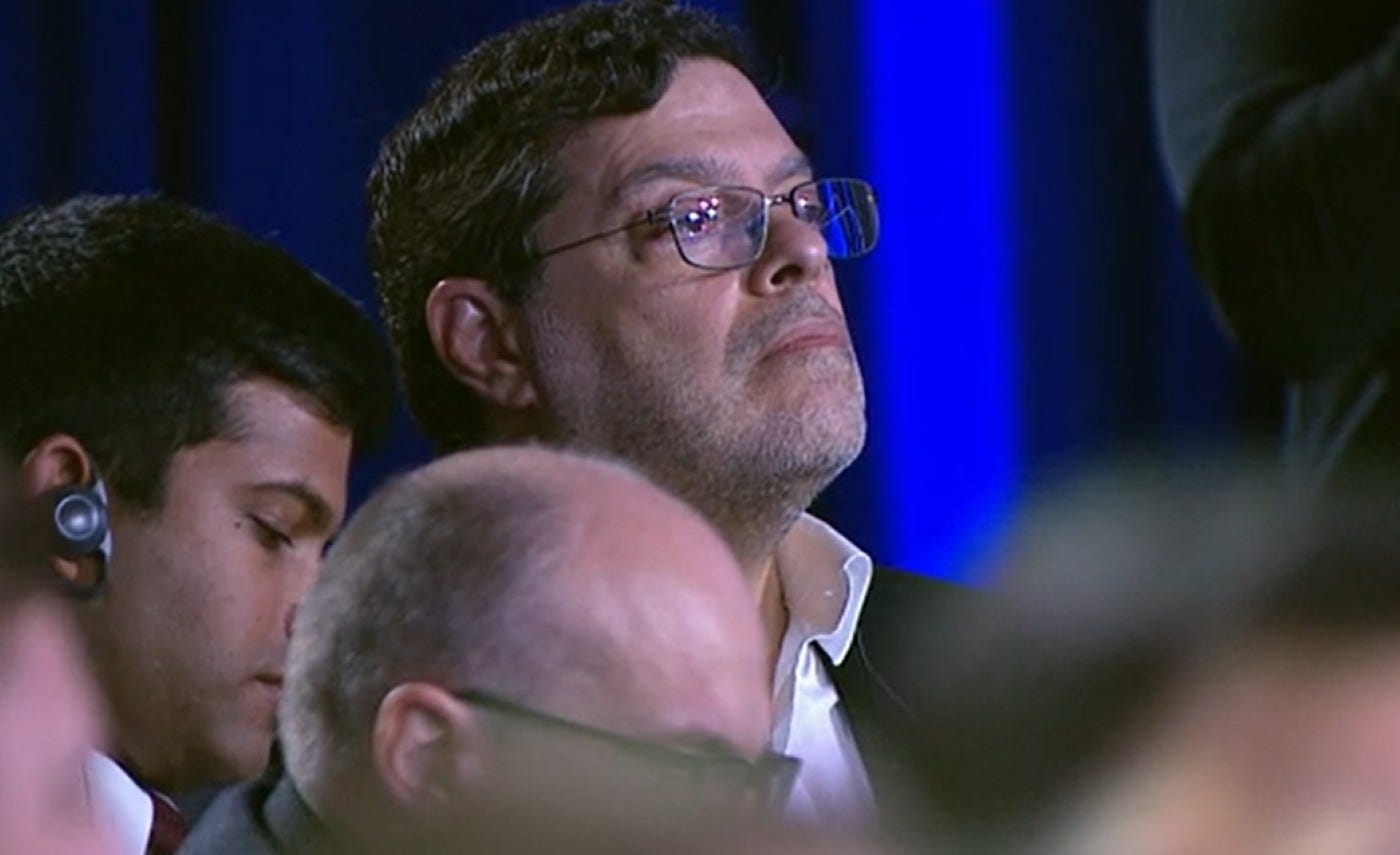

Putin’s speech at Valdai on October 2 was shared as Part 1 and Part 2. He then engaged in a marathon question and answer session that included Fyodor Lukyanov (Research Director of the Foundation for Development and Support of the Valdai International Discussion Club), Ivan Safranchuk (senior research fellow at the Institute of International Studies), Professor Seyed Mohammad Marandi (an American-Iranian political analyst) and others.

Fyodor Lukyanov: Mr Putin, thank you very much for such an extensive…

Vladimir Putin: Have I worn you out? Sorry.

Fyodor Lukyanov: Not at all, you have only just begun. (Laughter.) But you have immediately set the bar for our discussion very high, so naturally we will seize on many of the themes you have raised.

Especially since a truly polycentric, multipolar world is still only beginning to be described. As you rightly noted in your remarks, it is so complex that we can only grasp parts of it, like in an old parable where everyone touches a part of the elephant and thinks it is the whole, but in reality it is just one part.

Vladimir Putin: You know these are not just words. I was speaking from practice. I am often faced with very specific issues that need to be addressed in one part of the world or another. In the past, during the Soviet Union, it was one bloc versus another: you agreed within your bloc, and off you went.

No, I will be honest with you: more than once I have had to weigh a decision – to do this or that. But my next thought was: no, I can’t do that because it will affect someone; it would be better to do something else. But then: no, that would hurt someone else. That is the reality. Truth to tell, there were a few cases where I decided that we won’t do anything at all because the damage from acting would be greater than from simply showing restraint and patience.

This is the reality of today. I did not invent anything – it is just how things are in real life, in practice.

Fyodor Lukyanov: Did you play chess at school?

Vladimir Putin: Yes, I liked chess.

Fyodor Lukyanov: Good. Then I will continue from what you just said about practice. It is true: it is not only the theory that is changing, but also practical actions on the international stage can no longer be what they once were.

In previous decades many relied on institutions – international organisations, structures within states – that were set up to deal with certain challenges.

Now, as many experts noted at Valdai over the past few days, these institutions for various reasons are either weakening or losing their effectiveness altogether. This means that far greater responsibility falls on leaders themselves than in the past.

So my question to you: do you ever feel like Alexander I at the Congress of Vienna, personally negotiating the shape of the new world order – just you, alone?

Vladimir Putin: No, I do not. Alexander I was an emperor; I am a president, elected by the people for a specific term. That is a big difference. That’s my first point.

Second, Alexander I united Europe by force, defeating an enemy that had invaded our territory. We remember what he did – the Congress of Vienna, and so on. As for where the world went after that, let historians judge. It is debatable: should monarchies have been restored everywhere, as if trying to turn the wheel of history back a little? Or would it not have been better to look at emerging trends and lead the way forward instead? That is just by way of comment – apropos, as they say – not directly related to your question.

Regarding modern institutions, what is the problem, after all? They experienced degradation precisely during the period when certain countries, or the collective West, sought to exploit the post-Cold War situation by declaring themselves victors. In this context, they began imposing their will on everyone – this is the first point. Second, all others gradually, at first mutedly, then more actively, began to resist this.

During the initial period, after the Soviet Union ceased to exist, Western structures inserted a significant number of their own personnel into old frameworks. All these personnel, strictly following instructions, acted precisely as they were directed by their Washington bosses, behaving, frankly speaking, very crudely, disregarding everything and everyone.

This led to Russia, among others, ceasing altogether to engage with these institutions, believing that nothing could be achieved there. What was the OSCE created for? To resolve complex situations in Europe. And what did it all boil down to? The entire activity of the OSCE reduced to becoming a platform for discussing, for example, human rights in the post-Soviet space.

“Even the US State Department noted that human rights issues have emerged in Britain.” - Putin

Well, listen. Yes, there are plenty of problems. But are there not many in Western Europe? Look, it seems to me, just recently, even the US State Department noted that human rights issues have emerged in Britain. It would seem nonsensical – well, good health to those who pointed this out.

However, these problems did not just emerge; they have always existed. These international organisations simply began professionally focusing on Russia and the post-Soviet space. But that was not their intended purpose. And this is the case across many areas.

Therefore, they have largely lost their original meaning – the meaning they had when they were created in the previous system, when there was the Soviet Union, the Eastern bloc and the Western bloc. That is why they degraded. Not because they were poorly structured, but because they ceased performing the roles for which they were created.

Yet there is and was no alternative to seeking consensus-based solutions. Incidentally, we gradually came to realise that we needed to create institutions where issues are resolved not as our Western colleagues attempted to resolve them, but genuinely based on consensus, genuinely based on aligning positions. This is how the SCO – the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation – emerged.

What did it originally grow out of? Out of the need to regulate border relations between countries – former Soviet republics and the People’s Republic of China. It worked very well, indeed. We began expanding its scope of activity. And it took off! You see?

This is how BRICS emerged, when the Prime Minister of India and the President of the People’s Republic of China were my guests, and I proposed meeting as a trio – this was in St Petersburg. RIC emerged – Russia, India, China. We agreed that: a) we would meet; and b) we would expand this platform for our foreign ministers to work. And it took off.

Why? Because all participants immediately saw, despite some rough edges between them, that it was a good platform overall – there was no desire to push oneself forward, to advance one’s own interests at any cost. Instead, everyone understood that balance must be sought.

Soon after, Brazil and South Africa asked to join – and BRICS emerged. These are natural partners, united by a common idea of how to build relations to find mutually acceptable solutions. They began gathering within the organisation.

The same began happening worldwide, as I mentioned earlier regarding regional organisations. Look at how the authority of these organisations is growing. This is the key to ensuring that the new complex multipolar world nevertheless has a chance to be stable.

Fyodor Lukyanov: You have just now used a clear and popular metaphor about might being right unless there is a stronger might. It can also be applied to institutions, because when institutions are ineffective, you have to resort to might, that is, military force, which has again come to the fore in international relations.

It is often discussed, and we at the Valdai forum had a section that addressed this issue – the character of a new war, modern war. It has clearly changed. What can you, as supreme commander-in-chief and a political leader, say about changes in the character of war?

Vladimir Putin: It is a highly specific and yet an extremely important question.

First, there have always been non-military methods of dealing with military matters, but they are acquiring a new meaning and producing new effects with the development of technology. What I mean is information attacks and attempts to influence and corrupt the political mindset of the potential opponent.

Here is what has come to my mind right now. I have recently been told about the revival of an old Russian tradition, where young women go to parties, including in bars and clubs, wearing traditional Russian clothes and headdresses. You know, this is not a joke, and this makes me happy. Why? Because it means that our enemies have not attained their goal, despite all the attempts to corrupt Russian society from within, and even that the effect is the opposite of what they expected.

It is very good that our young people have this defence against attempts to influence the public mindset from within. It is proof of the maturity and strength of Russian society. But this is only one side of the coin. The other is the attempts to damage our economy, financial sector and so on, which is extremely dangerous.

As for the purely military component, there are many new elements related to technological development, of course. It is on everyone’s lips, yet I will say it again – it is unmanned vehicles that can operate in three domains – air, land, and sea. They include unmanned boats, unmanned ground vehicles, and unmanned aerial vehicles.

Moreover, all of them have a dual use. This is extremely important; it is one of the special modern features. Many technologies that are being used in combat have dual uses. Take the unmanned aerial vehicles, which can be used in medicine and to deliver food or other useful cargo everywhere, including during hostilities.

This calls for developing other systems as well, such as intelligence and electronic warfare systems. This is changing the tactics of warfare. Many things are changing on the battlefield. There is no use for Guderian’s wedge formations or Rybalko’s charges, which were carried out during World War II. Tanks are being used completely differently now, not to charge through enemy defences but to support the infantry, which is being done from covered positions. This is necessary too, but it is a different method.

But do you know what is most remarkable? The sheer swiftness of change. Technological paradigms can shift in a month, sometimes in a week. I have said this many times. Suppose we deploy a key innovation, such as high-precision weapons, including long-range systems, which are a vital component of modern warfare – and it suddenly grows less effective.

Why? Because the adversary has deployed even newer electronic warfare systems. They have analysed our tactics and adapted their response. Consequently, we now need to find an antidote within a matter of days, a week at most. This is happening with stunning regularity, and it has profound practical implications, from the battlefield itself to our research centres. This is the reality of modern armed conflict: a process of continuous upgrade.

Everything changes, except for one thing: the bravery, courage, and heroism of the Russian soldier. It is our immense source of pride. And when I say ‘Russian,’ I am not speaking solely of ethnicity or even the passport one holds. Our soldiers themselves have embraced this idea. Today, every one of them, regardless of religion or ethnic background, says with pride: “I am a Russian soldier.” And they are.

Why is this? I would like to answer by turning to Peter the Great. What was his definition? Who, in his eyes, was a Russian? For those who know the quote, you will recognise it. For those who do not, I will share it with you now. Peter the Great said: “He is Russian who loves and serves Russia.”

Fyodor Lukyanov: Thank you.

As for the headdresses, kokoshniks, I got the hint. Next time we will wear appropriate dress.

Vladimir Putin: You do not need a kokoshnik.

Fyodor Lukyanov: No? Good, as you say.

Mr President, on a more serious note, you spoke about the swiftness of change, and indeed, the pace is staggering, both in the military and civilian spheres. It seems clear that this accelerated reality is what will define the coming years and decades.

This brings to mind the criticism we faced more than three years ago, at the start of the special military operation. At that time, critics argued that Russia and its army were lagging behind in certain areas – and many of our less than successful steps were directly linked to that.

“We are effectively at war with the collective might of NATO. They are no longer even hiding this fact.” - Putin

This leads me to two key questions. First, in your view, have we since managed to close that gap?

And second, since we speak of the Russian soldier, what is your assessment of the current situation on the frontlines?

Vladimir Putin: First, let us be clear: it was not merely a ‘lag.’ There were entire fields where our knowledge was simply non-existent. The issue was not that we lacked the time to develop certain capabilities. The issue was that we were completely unaware that such capabilities were even possible.

Second, we are fighting this war and producing our own military equipment. But on the other side of the line, we are effectively at war with the collective might of NATO. They are no longer even hiding this fact. We see this in the direct involvement of NATO instructors and representatives from Western countries in the hostilities. A command centre has been established in Europe for the purpose of coordinating our adversary’s war effort: providing the Armed Forces of Ukraine with intelligence, satellite imagery, weapons, and training. And I must reiterate: these foreign personnel are not only involved in training; they are directly participating in operational planning and combat operations themselves.

Therefore, this presents a serious challenge for us, of course. But the Russian army, the Russian state, and our defence industry have rapidly adapted.

Now, I say this without any exaggeration – this is not hyperbole or empty boasting, but I am convinced that today, the Russian army is the most combat-ready army in the world. This holds true in terms of personnel training, technical capabilities, and our ability to both deploy and continuously upgrade them. It is true regarding our capacity to supply new weapons systems to the frontline, and even in the sophistication of our operational tactics. This, I believe, is the definitive answer to your question.

Fyodor Lukyanov: Our interlocutors – and your interlocutor across the ocean – have recently renamed their Department of Defence as the Department of War. Superficially, it may seem the same, but as they say, there is nuance. Do you believe names carry substantive significance?

Vladimir Putin: One could say no, but equally, one might observe that “as you name the ship, so shall it sail.” There is likely some meaning in this, though Department of War does sound rather aggressive. Ours is the Ministry of Defence – this has always been our position, remains so, and will continue to be. We harbour no aggressive intentions towards third countries. Our Ministry of Defence exists solely to safeguard the security of the Russian state and the peoples of the Russian Federation.

Fyodor Lukyanov: Yet he taunts us as a “paper tiger” – what about that?

Vladimir Putin: A “paper tiger”… As I have said, Russia has not been fighting the Armed Forces of Ukraine or Ukraine itself these past years, but effectively the entire NATO bloc.

Regarding your question about developments along the line of contact – I will return to these “tigers” shortly.

“Across virtually the entire line of contact, our forces are advancing with confidence.”

Presently, across virtually the entire line of contact, our forces are advancing with confidence. To begin from the north: the North Group of Forces – in the Kharkov Region, the town of Volchansk, and in the Sumy Region, the residential community of Yunakovka – have recently been brought under our control. Half of Volchansk has been secured – the remaining portion will inevitably follow shortly, as our fighters complete the operation. A security zone is being established methodically and according to plan.

The West Group of Forces has largely secured Kupyansk – a significant population centre (not fully, but two-thirds of the city). The central district is already ours, with engagements continuing in the southern sector. Another substantial town, Kirovsk, is now entirely under our control.

The South Group of Forces has entered Konstantinovka – a key defensive line comprising Konstantinovka, Slavyansk, and Kramatorsk. These fortifications were developed by the AFU over more than a decade with the assistance of Western specialists. Yet our troops have now penetrated these defences, with combat ongoing there. The same applies to Seversk, another major community where hostilities are underway.

The Centre Group of Forces continues effective operations, having entered Krasnoarmeysk – from the southern approach, if I recall correctly – with fighting now occurring within the town. I will refrain from excessive detail, not least because I have no desire to inform our adversary – paradoxical as that may sound. Why? Because they are in disarray, scarcely comprehending the situation themselves. Providing them additional clarity serves no purpose. Rest assured, our personnel are executing their duties with confidence.

As for the East Group of Forces: it is progressing decisively through the northern Zaporozhye Region and partially into the Dnepropetrovsk Region at a rapid pace.

The Dnieper Group of Forces likewise operates with full assurance. Approximately… Almost 100 percent of the Lugansk Region is ours – the enemy retains perhaps 0.13 percent. In the Donetsk Region, they control marginally over 19 percent. In the Zaporozhye and Kherson regions, this figure stands at roughly 24–25 percent, respectively. Everywhere, Russian forces – I emphasise – maintain undisputed strategic initiative.

Yet if we are combating the entire NATO alliance, advancing thus with unwavering confidence, and are deemed a “paper tiger” – what does that make NATO itself? What manner of entity is it then?

But never mind that. What matters most is to have confidence in ourselves – and we do.

Fyodor Lukyanov: Thank you.

There are paper cut-out toys for children – paper tigers. You can present one to President Trump when you meet next time.

Vladimir Putin: No, we have our own relationship, and we know what presents to give each other. You know, we have a very calm attitude towards this.

I do not know in what context that phrase was said; maybe it was said ironically. You see, there are some elements… So, he told his interlocutor that [Russia] is a paper tiger. What action could follow next? Actions could be taken to deal with that “paper tiger.” But nothing like this is happening in reality.

What is the current problem? They are sending enough weapons to the Armed Forces of Ukraine, as many as Ukraine needs. In September, the AFU’s losses amounted to about 44,700 people, nearly half of them irretrievable losses. In the same period, they forcibly mobilised slightly more than 18,000 people. Approximately 14,500 people have returned to the army from hospitals. If we add up these figures and subtract the total from the number of casualties, we will see that Ukraine lost 11,000 in one month. In other words, the number of its troops on the frontline was not replenished and is decreasing.

If we look at the figures from January to August, approximately 150,000 Ukrainians have deserted from the army. Over the same period, 160,000 people have been mobilised into the army, but 150,000 deserters is too many. Taken together with increasing losses, even though the figure was higher the previous month, this means that the only solution is to lower the mobilisation age. But this will not produce the desired result either.

Russian and, incidentally, Western experts believe that this will hardly have a positive effect because they have no time to train the conscripts. Our forces are advancing every day, you see? They have no time to become entrenched or train their new personnel, and they are also losing more servicemen than they can replenish on the battlefield. That is what matters.

Therefore, the Kiev leaders should think more seriously about reaching an agreement. We have said this many times, offering them the opportunity to do so.

Fyodor Lukyanov: Do we have enough personnel for everything?

Vladimir Putin: Yes, we do. First, we also sustain losses, regrettably, but they are several times smaller than the AFU’s losses.

And then, there is a difference. Our men volunteer for military service. They are actually volunteers. We are not conducting a sweeping mobilisation, let alone a forced one, unlike the Kiev regime. I have not invented this; trust me, this is objective data, confirmed by Western experts: 150,000 deserters [from the AFU] from January to August. What is the reason? People have been seized in the street, and now they are deserting from the army, and rightfully so. Moreover, I am urging them to desert. We also call on them to surrender, which is difficult to do because those who try to surrender are shot by Ukrainian anti-retreat or barrier units or killed by drones. And drones are often operated by mercenaries from other countries who kill Ukrainians because they do not care about them. As for the [Ukrainian] army, it is a simple army made up of workers and farmers. The elite is not fighting; it is only sending its own citizens to the slaughter. That is why there are so many deserters.

We also have deserters, which is normal for armed conflicts. Some people leave their units without permission. But there are few of them, really few, compared to the other side, where desertion has become a massive issue. That is the problem. They can lower the mobilisation age to 21 or even 18 years, but this will not resolve the problem, and they must accept this. I hope the Kiev regime’s leaders will come to see this and will find the strength to sit down at the negotiating table.

Fyodor Lukyanov: Thank you.

“Nothing particularly surprised me, as I had foreseen much of what would unfold.”

Fyodor Lukyanov: Friends, please ask your questions. Ivan Safranchuk, go ahead, please.

Ivan Safranchuk: Mr President, thank you very much for your highly interesting opening remarks. You have already set a high bar for our discussion during your exchange with Fyodor Lukyanov.

This topic was briefly touched upon in your earlier comments, but I would like to seek clarification. Amid the fundamental changes that have occurred in recent years, has anything genuinely surprised you? For instance, the sheer fervour with which many Europeans have pursued confrontation with us, and how some have ceased to feel ashamed of their participation in Hitler’s coalition.

After all, there are developments that were hard to imagine until recently. Was there genuinely an element of surprise – how could this happen? You noted that in today’s world, one must be prepared for anything, as anything can occur – yet until recently, there seemed to be greater predictability. So, amidst this rapid pace of change, was there anything that truly astonished you?

Vladimir Putin: Initially… On the whole, broadly speaking, no, nothing particularly surprised me, as I had foreseen much of what would unfold. Nevertheless, what did astonish me was this readiness – even eagerness – to revise everything that had been positive in the past.

Consider this: at first, very cautiously, with probing, the West began equating Stalin’s regime with the fascist regime in Germany – the Nazi regime, Hitler’s regime – placing them on the same level. I observed all this clearly; I was watching. They began dredging up the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, while sheepishly forgetting about the Munich Betrayal of 1938, as though it never happened, as though the Prime Minister [of Great Britain] did not return to London after the Munich meeting and wave the agreement with Hitler from the aircraft steps – “We’ve signed a deal with Hitler!” – brandishing it – “I’ve brought peace!” Yet even then, there were those in Britain who declared: “Now war is inevitable” – that was Churchill. Chamberlain said: “I’ve brought peace.” Churchill retorted: “Now war is inevitable.” Those assessments were made even then.

They said: the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact – an atrocity, colluding with Hitler, the Soviet Union conspired with Hitler. Well, but you yourselves had conspired with Hitler shortly before and carved up Czechoslovakia. As though that never occurred. Propagandistically – yes, one can hammer these false equivalences into people’s heads, but in essence, we know how it truly was. That was the first act of the Ballet de la Merlaison.

Then matters escalated. They began not merely equating Stalin’s and Hitler’s regimes – they attempted to erase the very outcomes of the Nuremberg Trials. Bizarre, given that these were participants in a shared struggle, and the Nuremberg Trials were collective, held precisely so that nothing similar would recur. Yet they began doing that. They started tearing down monuments to Soviet soldiers and so forth, those who fought against Nazism.

I understand the ideological underpinnings here. I stated from this podium earlier that when the Soviet Union imposed its political system on Eastern Europe – yes, all this is clear. But the people who fought Nazism, who gave their lives – what have they to do with it? They were not leading Stalin’s regime, they made no political decisions, they simply laid down their lives on the altar of Victory over Nazism. They began this – and then further, and further…

Yet this did still surprise me – that there seems no limit, purely, I assure you, because this concerns Russia, and the desire to somehow marginalise it.

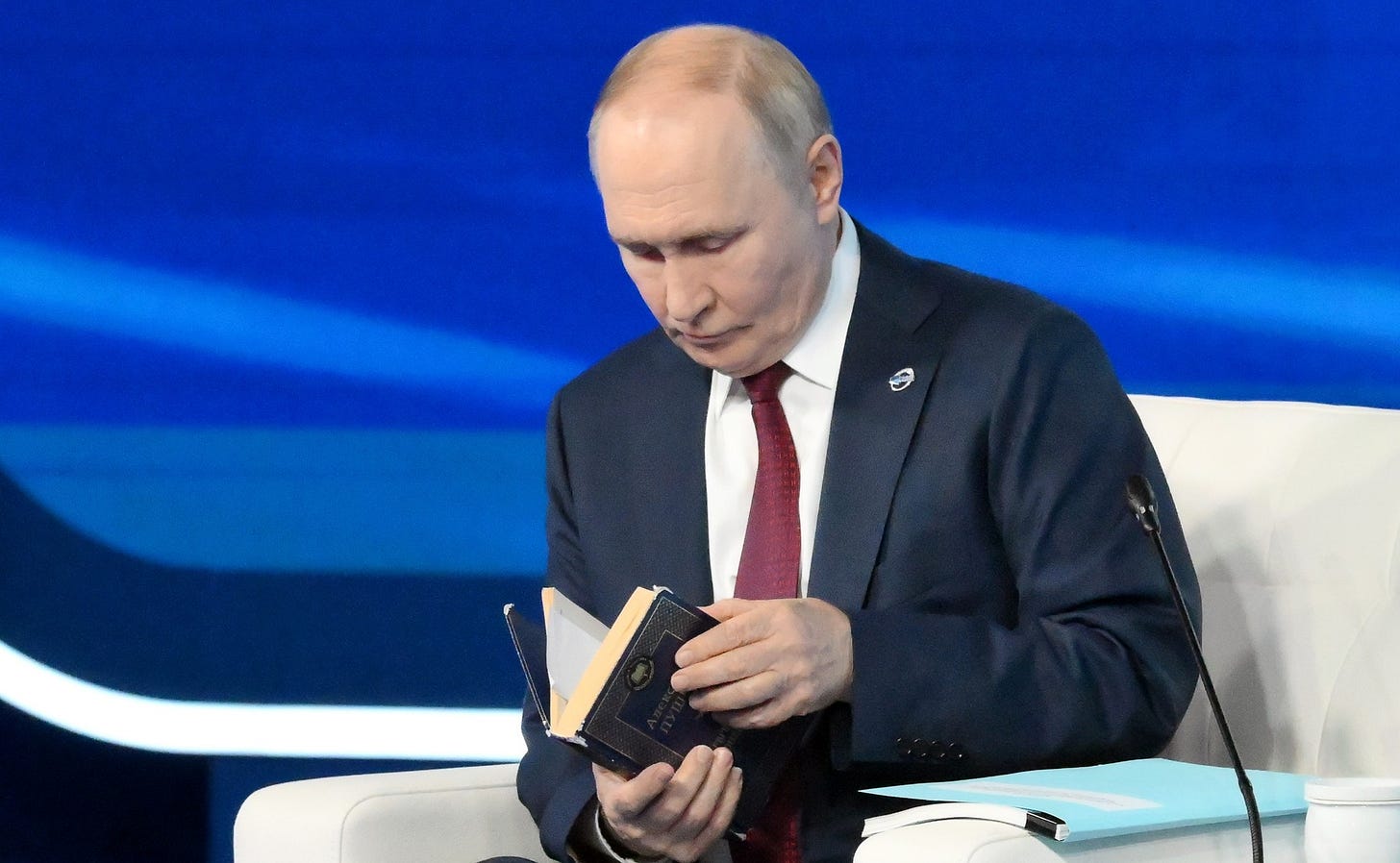

You see, I had intended to approach the podium, but I did not bring my book with me – I had planned to read something to you, yet I simply forgot and left it behind. What do I wish to convey? On my desk at home lies a volume of Pushkin. I occasionally enjoy immersing myself in it when I have five spare minutes. It is intrinsically interesting, pleasant to read, and moreover, I relish delving into that atmosphere, sensing how people lived back then, what inspired them, and what they thought.

Just yesterday, I opened it, leafed through, and came across a poem. We all know – the Russians [among those present here] certainly do – Mikhail Lermontov’s Borodino: “Hey tell, old man, had we a cause …”, and so forth. However, I never knew Pushkin had written on this theme. I read it, and it made a profound impression, for it reads as though Pushkin penned it yesterday, as if he were telling me: “Listen, you are going to the Valdai Club – take this with you, read it to your colleagues, share my thoughts on the matter.”

Frankly, I hesitated, thinking: very well. But since the question arose, and I have the book with me – may I? It is fascinating. This answers many questions. It is titled The Borodino Anniversary:

The great day of Borodino

With brotherly commemoration

We’d thus proclaim: “Did not the tribes advance

and threaten us with devastation?

Was not all Europe gathered here?

And whose star led them through the air?

Yet firm we stood, with steadfast tread,

And met with breast the hostile tide

Of tribes ruled by that haughty pride

And equal proved the unequal fight.

And now? Their disastrous flight,

Boastful, they now forget outright;

Forgot the Russian bayonet and snow,

Which buried their fame in desert wastes below.

Again they dream of feasts to come –

For them, Slav blood is drunken wine

But bitter shall their morning be

But long such guests’ unbroken sleep,

Within a cramped and cold new home,

Beneath the turf of Northern soil!

[Applause]

Everything is articulated here. Once again, I am convinced that Alexander Pushkin is our everything. Incidentally, Pushkin grew quite impassioned later – I will not read that, but you may do so if you wish. This was written in 1831.

You see, Russia’s very existence displeases many, and all wish to partake in this historic endeavour – inflicting a “strategic defeat” upon us and profiting thereby: taking a bite here, a bite there… I am tempted to make an expressive gesture, but there are many ladies present [in the hall]… That will not happen.

Fyodor Lukyanov: I wish to note a highly significant parallel. Poland’s President Nawrocki literally said – I believe just the day before yesterday in an interview…

Vladimir Putin: By the way, Poland is mentioned later [in the poem].

Fyodor Lukyanov: Yes, well, naturally – our favourite partner. So, he stated in the interview that he regularly “converses” with General Piłsudski, discussing matters, including relations with Russia. Whereas you – with Pushkin. It seems somewhat discordant.

Vladimir Putin: You know, Piłsudski was such a figure – he harboured hostility towards Russia, and so forth – and under his leadership, guided by his ideas, Poland committed many errors prior to the Second World War. After all, Germany proposed resolving the Danzig and Danzig Corridor matters peacefully – Poland’s leadership at the time categorically refused and ultimately became Nazism’s first victim.

They also wholly rejected the following – though historians surely know this – Poland then refused to allow the Soviet Union to assist Czechoslovakia. The Soviet Union was prepared to do so; documents in our archives attest to this – I read them personally. When notes were sent to Poland, Poland declared it would never permit Russian troops passage to aid Czechoslovakia, and that should Soviet aircraft fly over, Poland would shoot them down. In the end, it became Nazism’s first victim.

If today’s highest-ranking political family in Poland also remembers this, comprehending all the complexities and vicissitudes of historical epochs and bearing it in mind while consulting Piłsudski, and heeds these mistakes – then that would indeed be no bad thing.

Fyodor Lukyanov: Yet one suspects his context is rather different.

Right. Next question, colleagues, please. Professor Marandi, Iran.

Seyed Mohammad Marandi: Thank you very much for the opportunity, Mr President, and I thank Valdai as well, this excellent conference.

We are all saddened because during the last two years we’ve seen genocide in Gaza, and the pain and suffering of women and children being torn apart day and night. Recently we saw President Trump gave a peace proposal that looked more like a submission and capitulation. And especially introducing someone like Blair with his history is insult to injury. I was wondering what do you think the Russian Federation can do to bring an end to this misery, which has really darkened the days of everyone? Thank you.

Vladimir Putin: The situation in Gaza is one of the most tragic events in recent history. It is also well known that the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has publicly admitted – and he often reflects Western views – that Gaza has become the largest children’s cemetery in the world. What could be more tragic? What could be more painful?

Now, regarding President Trump’s proposal on Gaza – you may find this surprising, but Russia is overall ready to support it. Provided, of course, that it truly leads to the ultimate goal we have always spoken about. We must thoroughly examine the proposals made.

Since 1948 – and later in 1974, when the relevant UN Security Council resolution was adopted – Russia has consistently supported the creation of two states: Israel and a Palestinian state. I believe this is the only key to a final, lasting solution to the Palestinian–Israeli conflict.

As far as I understand – I have not looked through the proposal carefully yet – it suggests creating an international administration to govern Palestine for some time, or more precisely, the Gaza Strip. It is proposed that Mr Blair would head it. Now, he is not known as a great peacemaker. But I know him personally. I have even visited him at his home, spent the night there, and in the morning, over coffee in our pajamas, we spoke at length. Yes, this is true.

Fyodor Lukyanov: Was the coffee good?

Vladimir Putin: Yes, quite good.

But what would I like to add? He is a man with strong personal views, but he is also an experienced politician. Overall, if his knowledge and experience are directed towards peace, then yes, of course, he could play a positive role.

However, several questions naturally arise. First: how long would this international administration operate? How, and to whom, would power then be transferred? As I understand it, this plan foresees the possibility of eventually transferring power to a Palestinian administration.

I believe it would be best to transfer control directly to President Abbas and the current Palestinian administration. Perhaps they may face difficulties in addressing security matters. But as I heard from colleagues today, this plan also envisages that the power transfer may involve local militia groups in order to ensure security. Is that bad? In my opinion, this could be a good solution.

Let me repeat: we must understand how long this international administration will be in force. What is the timeframe for the transfer of civilian authority? No less important are security issues. I believe that this deserves support.

On one hand, we are talking about the release of all hostages held by Hamas, and on the other – the release of a significant number of Palestinians from Israeli prisons. It must also be made clear: how many Palestinians, who exactly, and in what timeframe this exchange would take place.

And, of course, the most important issue: how does Palestine itself view this proposal? This is absolutely essential. Here, the opinion of the region and the entire Islamic world matters, but most of all Palestine itself and the Palestinians, including Hamas. There are different attitudes toward Hamas, and we also have our own position and contacts with them. It is important for us that both Hamas and the Palestinian Authority support such an initiative.

All these questions require thorough and careful study. But if this plan is implemented, it would indeed represent a significant step towards settling the conflict. Still, I want to stress once again: the conflict can only be fundamentally resolved through the creation of a Palestinian state.

Of course, Israel’s position will be crucial here. We do not yet know how it has reacted. Frankly, I have not seen any public statements yet; I simply have not had time to look. But what really matters is not public rhetoric, but how the Israeli leadership reacts to this and whether it is ready to implement what is being proposed by the US President.

There are many questions here. But overall, if all these positive elements I have mentioned come together, it could become a real breakthrough. Such a breakthrough would be very positive.

Let me repeat this for the third time: the creation of a Palestinian state is the cornerstone of any comprehensive settlement.

Fyodor Lukyanov: Mr President, were you surprised when a couple of weeks ago a US ally, Israel, attacked another US ally, Qatar? Or is that just considered normal now?

Vladimir Putin: Yes, I was surprised.

Fyodor Lukyanov: And what about the US reaction? Or rather, the lack thereof? How did you take that?

(Vladimir Putin throws up his hands.)

I see. Thank you.

Tara Reade, please.

Tara Reade, Russia Today: Good afternoon. President Putin, it’s a tremendous honour to speak to you. I want to start with a thank you that will lead to the question.

I used to work for Senator Biden and Leon Panetta in the United States of America, and I came forward about some things and corruption in 2020, and I was targeted by the Biden regime to the point where I had to flee.

Margarita Simonyan, who is a hero to me, helped me and Masha, Maria Boutina, get through. And I was able to get political asylum thanks to you. And with your collective effort, you saved my life.

So thank you. I was a target, and my life was in immediate danger. What I can say about Russia is, (in russian) люблю Россию (I love Russia). (In english) I have found it to be beautiful. The propaganda in the West was wrong about Russia. I love Moscow. The people have been very warm and welcoming. It’s efficient, and for the first time, I feel safe, and I feel more free.

I work for RT and I’ve really enjoyed it. I’m given a lot of creative freedom to work in my sphere in geopolitical analysis. And so thank you to the Valdai Club for recognising my intellectual pursuits. I appreciate you. So this is my question. I have met other Westerners that have come here for sanctuary to Russia, also for economic reasons and for shared values.

How do you feel about watching this stream of Westerners coming in asking to live in Russia, and will it be easier to get Russian citizenship? And you gave me, by presidential decree, Russian citizenship, which is a tremendous responsibility and honour. So, I am Russian. Thank you very much.

Vladimir Putin: You have mentioned shared values. And how do we treat those people who come here from Western countries, want to live here, and share these values with us? You know, our political culture has always had both positive and controversial aspects.

In the identity documents of subjects of the Russian Empire, there was no line for “Nationality.” It simply was not there. In the Soviet passport it appeared, but in the Russian passport – again, it was not there. And what was there? “Religion.” There was a common value, a religious value, an affiliation with Eastern Christianity – with Orthodoxy, faith. There were other values as well, but this was the defining one: what values do you share?

That is why even today, it makes no difference to us whether a person comes from the East, the West, the South, or the North. If they share our values, they are our people. That is how we see you, and that is why you feel the attitude towards yourself. And that is how I see it as well.

As for administrative and legal procedures, we have taken the necessary decisions to make it easier for people who wish to live in Russia, to tie their lives to our country, even if only for some years, for a longer period, to do so. These measures reduce administrative barriers.

I cannot say that we are seeing an enormous influx. Still, it amounts to thousands of people. I think around 2,000 applications have been submitted, 1,800 or so, and about 1,500 approved. And the flow continues.

Indeed, people are coming, motivated not so much by political reasons, but rather by values. Especially from European countries, because what I would call “gender terrorism” against children there does not sit well with many people, and they are looking for safe havens. They come to us, and God grant them success. We will support them as far as we can.

You also said – I made a note – “I love Russia,” “I love Moscow.” Well, we have much in common, because I also love Moscow. That is the basis we will build on.

Fyodor Lukyanov: From a native of St Petersburg, of Leningrad, that means a lot.

Vladimir Putin: A revolutionary development.

Read Part 2.